Our Lady of Saydnaya Patriarchal Monastery

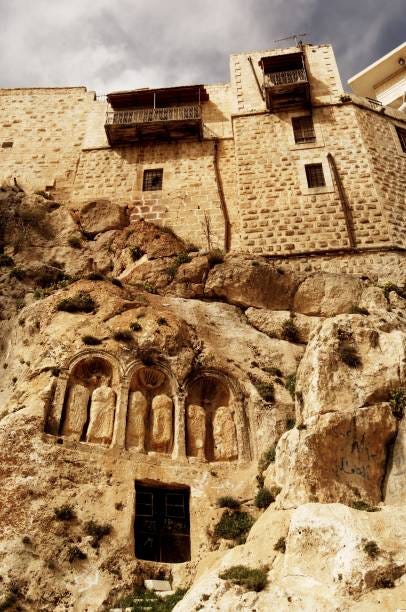

Our Lady of Saydnaya Monastery of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch, one of the most ancient monasteries in the world and in the Middle East, was built by Greek Emperor Justinian I in 547 AD.

Antioch Patriarchate | Our Lady of Saydnaya Monastery | Syria

Our Lady of Saydnaya Patriarchal Monastery

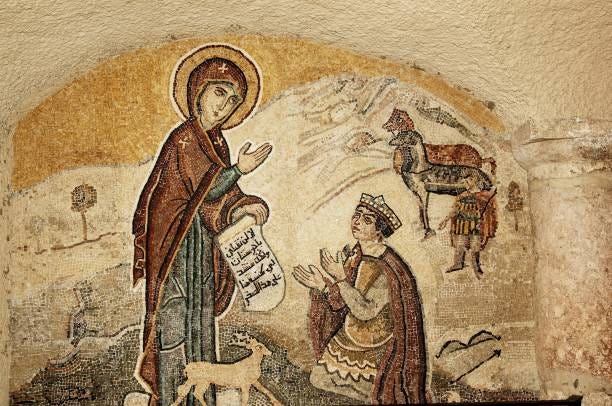

The Syrian town of Saydnaya has more than forty churches, chapels, and monasteries. The most prominent among them is the convent of the Virgin Mary, one of the most important institutions in the Patriarchate of Antioch. Since the Middle Ages, most pilgrims and travellers on their way to the Holy Land would stop at Saydnaya in order to pray before the miraculous icon of the Virgin and to receive her blessing. According to tradition, this image was painted by St Luke himself, and many miracles have been attributed to it in the course of time.

Saydnaya lies in the district of Damascus at an altitude of 1350 metres, about twenty-five kilometers north of Damascus on the slopes of Mount Qalamoun. The town was frequently praised by visitors for its beauty; in recent times, however, it has become congested with drab apartment blocks.

The name of Saydnaya has been differently interpreted, and it may have more than one meaning. Local tradition holds that Saydnaya means ‘Halting-place of the gazelle’. The place-name has also been thought to mean Our Lady the New, from the Greek nea, ‘new’, and the Arabic sayyida, ‘lady’. However, the word sayd is generally related to hunting, and naya is a typical place-suffix in Syriac; therefore, Saydnaya probably means simply a hunting-place. Indeed, in ancient times, a temple of Saydoun, the Phoenician god of the hunt, stood in this once densely forested region. Under later Christian and Arabic influence, perhaps the name may have been thought to mean the ‘place of the Lady’.

In the oldest records, the site is named Sad Manaia. But later manuscripts give many variations. In the Crusader period, it was known as the convent of Our Lady of Sardenay or Our Lady of the Rock. In the fifteenth century, the name Sardenayra appears; in the seventeenth, Sidenaia; finally, it became Saydnaya.

The convent of Saydnaya is specially distinguished for its hospitality. Orthodox families of Damascus and other cities traditionally spent the summer there. The convent maintains an orphanage for girls, which now houses 37 orphans. It is managed by five Religious, directed by Sister Febronia. In 1948, the mother superior, Maria Hassoun el-Maalouf from Bikfaya in Lebanon, founded a school for the nuns and established an order consisting of pupils from the orphanage. The school was officially recognized in 1950, and it offers a scientific diploma accredited by the Patriarchate.

Since medieval times, the nuns have worn garments of wool and cotton, bound at the waist by a large leather belt. Each nun is assigned her own cell for the duration of her residence, and she is responsible for its furnishing and maintenance. It normally has a small kitchen and bathroom attached.

The Religious perform the morning and evening offices when the bell of Our Lady rings. During fasting periods, the office is performed four times a day. Three times a day, the bell calls the Religious for meals. They usually eat together in the refectory, but some prefer to remain alone and are served in their cells. During the daytime, the nuns continue their religious duties but also practice their own activities, such as knitting, embroidery, and the manufacture of small religious objects for sale. Today, however, their work centers around the art of icon-restoration, which is flourishing. In addition, five nuns specialize in the making of clerical vestments, and others take care of pilgrims and visitors. In summer and on feast-days, up to 350 people are housed in the convent.

The convent still owns much land in Syria and Lebanon, and the nuns grow much of their food. The cellars below the cells contain all the convent’s annual provisions, most of which are supplied by its own harvest. Large quantities of cereals, flour, dry vegetables, and other goods are preserved here in huge masonry tanks to provide for the needs of nuns, orphans, and visitors. Four wells under the basement of the convent give an ample supply of water.

The convent celebrates the feast of the Mother of God each year on her birthday, 8th September. This is an exceptional day for the whole town, which is filled with visitors from all over Syria and Lebanon. They are welcomed by the inhabitants of Saydnaya, who sometimes leave their own homes to visitors while they go out into the street to join the crowd of believers. Following tradition, the mother superior sends a group of people bearing a banner of the Holy Cross to welcome visitors at the column in the center of the town. All the pilgrims gather there to begin the procession with the banner in front, singing hymns and lighting fireworks. A special fasting period of eight days is observed throughout the Patriarchate of Antioch in honor of the convent of Saydnaya.

Apart from such great pilgrimages, individual pilgrims frequently visit for a few days. Visitors come from all over Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, and even from Western countries, to pray to the Mother of God and receive her blessing. Many Christian Arab families customarily make vows to baptize their children at Saydnaya, and Christian Jordanian tribes come regularly in September to baptize all infants born to them during the preceding year. The practice of hospitality still survives in the rule fixed to the doors of all the visitors’ cells, and the traveler who spends the night is asked to leave a donation of his choice in return for the maintenance of the convent.

History

Saydnaya’s origin is lost in time. Some remains from the classical period have been found, including temple ruins and Greek inscriptions. The Qalamoun region received Christianity in the time of St Paul, and the Aramaic language spoken by its inhabitants until the twelfth century is derived from the language spoken at the time of Christ. Melkite (Greek Orthodox) manuscripts in Syriac were written at Saydnaya until the eighteenth century. The influence of Aramaic is noticeable in the Arabic dialect used by the people of Saydnaya, and the neighboring people of Christian Maaloula and two other villages, once Christian but now Muslim, continue to speak the Aramaic language. The people of Qalamoun stubbornly preserve their authentic tradition and their ties to early Christianity.

According to tradition, the monastery was built by the Emperor Justinian I (527-565). Legend relates that while the emperor was hunting in the Qalamoun region, he saw a vision of the Virgin Mary, who ordered him to build a convent on the high rock upon which she was standing. The next day, Justinian began work on the foundations of the convent of Saydnaya, and when it was completed, the emperor’s sister Theodosia became its first superior.

There is no contemporary evidence, however, that Justinian founded the convent. The walls of Saydnaya have no trace of sixth-century origin, and Procopius of Caesarea (d. 561), the companion and official historian of Justinian, does not mention the foundation of the convent. Medieval Christian historians make no mention of Justinian, recording instead that the convent was founded by a widow of Damascus during the Byzantine period, who withdrew to lead a hermit’s life in Qalamoun.1 Without firm evidence connecting Saydnaya to the relatively well-documented Early Byzantine period, it remains impossible to speak with certainty about the origin of the convent.

The famous icon of the Virgin at Saydnaya, the Shaghoura, is attributed to the hand of St Luke the Evangelist, doctor and painter. Luke is traditionally regarded as the first icon-painter, who painted three miraculous icons of the Virgin after Pentecost in the fullness of the Holy Spirit. This tradition dates from the Iconoclastic Controversy of the eighth and early ninth centuries.

Although many churches were destroyed in Syria and Egypt in 1014, at the orders of the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-‘Amr-Allah, there is no mention of Saydnaya, and it was probably spared. The convent is first mentioned in a report addressed in 1175 to the emperor Frederick I Barbarossa by Burchard of Strasbourg, ambassador to the court of Saladin.2 An entire paragraph of this document describes the convent of Sardenay and recounts its history. From the start of the thirteenth century, poets and minstrels popularized the remarkable story of this Orthodox sanctuary in the East, and it began to draw Western pilgrims in large number.

During their rule in Syria from 1250 to 1517, the Mamluks destroyed many churches and monasteries, but Saydnaya was spared. Two Arab writers of this period mention it: Chehab al-Din al-Umari (fourteenth century) praises the rich gifts he received from its inhabitants and notes that pilgrimage to the Holy Land normally included a visit to Saydnaya;3 the other, Yaqut al-Hamawi (fifteenth century), lauds the convent’s vineyards and good wines.4

Russian travellers give much information about Saydnaya’s history. During the early Ottoman period, the convent was abandoned by monks and inhabited only by nuns because of the heavy taxation imposed by the authorities. In 1560, the patriarch Joachim ibn Jum‘a wrote to the tsar of Russia, Ivan IV the Terrible, requesting assistance for Saydnaya. Thirty years later, a monk brought 120 pieces of gold from the tsar to the sixty nuns at Saydnaya.

Waqf documents written at the start of the seventeenth century cite the name of the mother superior, Marthe, daughter of Haji Sa’ad. In 1636, Saydnaya was restored without the permission of the Turkish authorities: its superior Moses was imprisoned, tortured, and forced to pay a large fine. In 1656, the Patriarch of Antioch, Makarios al-Za‘im, visited Moscow and received special letters from the tsar, authorizing the grant of Russian alms to the monasteries of St George al-Homeyra, Balamand, and Saydnaya.

In 1708, there were forty nuns with a superior, and fifteen monks. The superior and monks spent the nights in the village, working and praying in the convent during the daytime.

In 1762, three years after a strong earthquake that destroyed many churches and mosques in Damascus, the convent was rebuilt by special permission of the Ottoman mufti of Damascus, Sheikh ‘Ali al-Muradi, through donations made by Damascene notables. It was rebuilt on a triangular plan with eighty cells. The church had four altars, one of which was reserved for the Jacobites (Syriac Orthodox) who came to venerate the miraculous icon of the Virgin. In 1768, the chronicler Mikha’il Burayk was designated as superior at Saydnaya.

A traveler who visited Syria in 1825 tells that only two years beforehand, the convent had narrowly escaped destruction in retaliation for the Greek Declaration of Independence in 1821.5 In 1840, the Russian consul Uspensky saw thirty-eight nuns at Saydnaya and noted that the convent’s revenues went to the patriarchate. In his time, many smaller neighboring monasteries, such as those of St Barbara, St George, St Thomas, and St Christopher, were affiliated to Our Lady of Saydnaya.

A large number of Syriac manuscripts preserved at the convent were burned at the start of the nineteenth century. The perpetrators intended to prevent Jacobite claims to ownership of the convent and indeed to efface memory of the Syriac language, which was still heard at Saydnaya by eighteenth-century travellers such as Browne, Ritter, and Volney.6

The nuns of Saydnaya have always been dedicated to hard work. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, they worked especially in silk cultivation, and the eighteenth-century traveler Bishop Pococke records that the mother superior showed him her rough and calloused hands. The convent has usually housed a sizeable number of Religious. Twenty-three were recorded in 13847 and twenty-four in 1598.8 About forty Religious were counted by travellers in 1735.9 Pococke, who visited soon afterwards, records that the Religious Sisters numbered twenty, supervised by two male Religious. The English cleric and traveller J. L. Porter noted in 1852 that the convent housed forty Religious and the superior, and the same number was recorded in 1930.10 There are thirty-eight Religious Sisters at the convent today.

Habib al-Zayyat, pp. 23-25.

Peeters, Paul, ‘La légende de Saidnaia’, Analecta Bollandiana 85.2 (1926), p. 138.

Shihab al-din al-‘umari, Mamalik al-absar, p. 356.

Yaqut al-hamawi, Mu‘jam al-buldan.

Habib al-Zayyat, p. 10.

Volney, Voyage en Syrie et en Egypte (Paris, 1787), vol. 1, p.331-2; Browne, W.G., Nouveau voyage en Egypte, en Syrie, et en Afrique (1792-1798) (Paris, 1800), p.242; Ritter, K., Die Erdkunde (Berlin 1854-5), pp. 254-255.

Leonardo Frescobaldi, p. 168.

Don Aquilante Rochetta, p. 90.

Van Egmond and H. Heyman, p. 261.

Porter, J. L., Five Years in Damascus (London, 1870), p. 130.